By now, it’s clear that artificial intelligence will radically alter our economic, political and social lives. It’s less clear what these changes will entail. Are we hurtling ineluctably toward violent extinction at the hands of superhuman robot overlords? Are we realizing the “fully automated luxury communism” dream? Neither of the above? Something in between?

The best way to get a sense for where AI is heading is to talk to those successfully building with it. Amjad Masad, the CEO and Founder of Replit, is one of those people. Replit is an online coding environment that Masad began building in college as a side project. Today, the company is worth over $1 billion and has tens of millions of users worldwide.

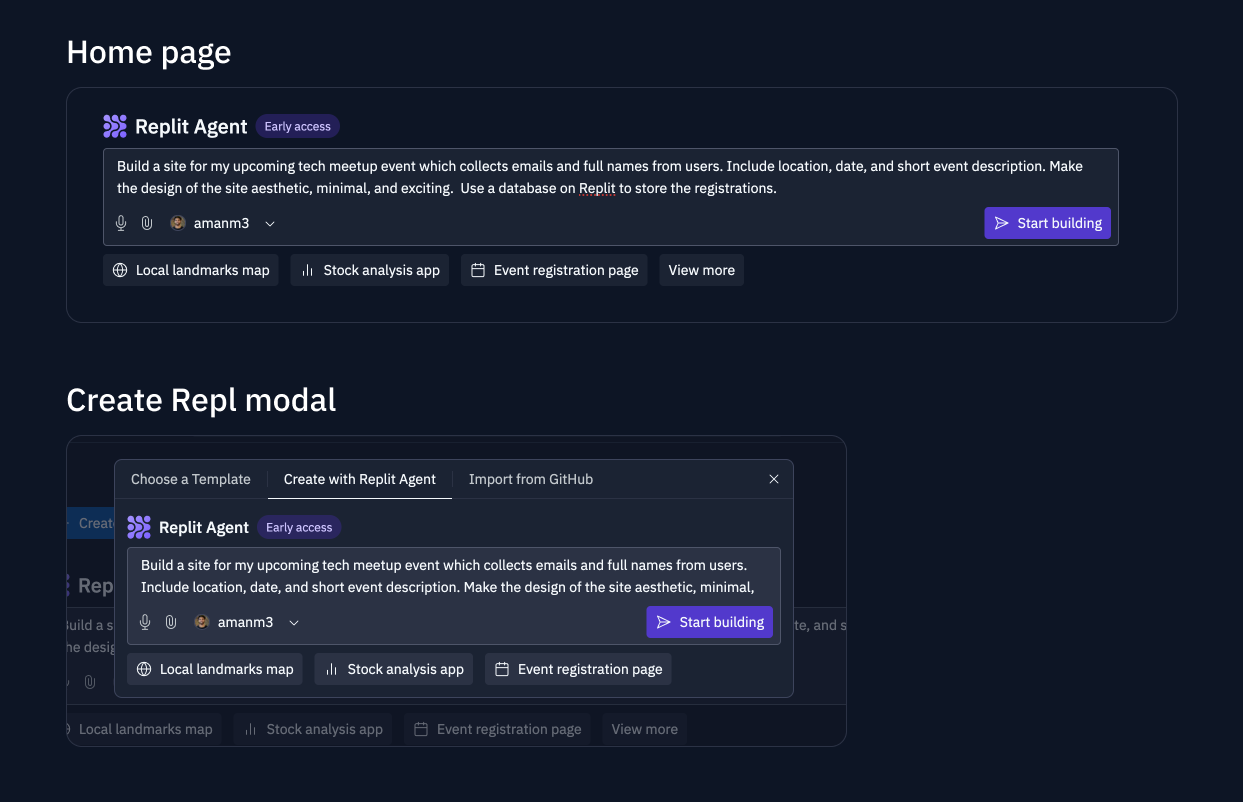

In September, Replit launched Replit Agent, an AI system that can create and deploy web applications given natural language prompts. You tell the agent what you want to build, and it will configure a development environment, install dependencies, execute code, and iteratively incorporate your feedback. In other words, it allows those with no programming experience to build their own software. All you need is internet connection and an idea.

Masad thinks this technology marks the start of a “personal software revolution” — a profound shift in how most people interact with software akin to the personal computer revolution of the 1980s. This past October, I sat down with him at Replit’s office in Foster City to discuss this revolution, how Replit Agent fits into it, and what implications it might have for society at large. Our conversation follows below.

Sanjana: Could you briefly introduce yourself? Also, I noticed that you call yourself “civilizationist” in your bio on X. What does that mean?

Amjad: You're actually the first person to ask me about that, which is curious, I thought it would come up sooner. It’s always hard to know how far to go when someone asks you to introduce yourself. How far do you go?

Sanjana: I guess a brief introduction would do, because I assume people reading this will know your professional background.

Amjad: Ok, I grew up in Jordan. I got into computers at a really young age — six years old. I remember my father bought a computer home. We were probably one of the few households in Amman that had a computer. It wasn’t like we were rich or anything, quite the opposite, but my father was really excited about computers.

That was one of my earliest memories. I don't remember many earlier memories. But I do remember standing there and watching my father set up the computer. I remember walking up to it and seeing him type something and watching the computer respond. It felt like he was having a conversation with the computer.

Pretty quickly, I learned a few commands and learned that I could model what a computer was in my mind. I realized that I was quite talented at modeling what a computer was and what it could do – that I was quicker than other people.

I went on to do programming in school, study computer science in college, and then came to the U.S., where I worked at startups and big tech, and then started this company, Replit.

Replit’s mission is to make programming more accessible, but we try to put a more ambitious spin on it, which is: Our mission is to create a billion software creators. We want to empower a billion people to create software.

Now, on the “civilizationist” front…I think the fact that we have civilization is pretty amazing. It’s an unlikely event. A lot of what led to the creation of civilization feels very fragile. We saw that instability during COVID, when the world came to a halt, and it just made me realize that civilization is even more fragile — more special — than we actually realize.

It’s easy for it to end, and for things like human rights to disappear. For a moment in time, I thought the ideas of the Enlightenment were universal and it just feels like they’re not. Increasingly, it feels easy for the world to devolve into a dark place — and so, what I really care about is that my kids, and other people’s kids, grow up in a world that is at least as good of a place as we grew up in, and hopefully better.

Maybe that also gets at why I get so annoyed at AI doomers. I think there are so many other things that we could be doing to make the world a better place, and I feel like AI killing everyone is the least of our concerns.

Sanjana: [Laughs] We’ll get to that. But I want to start by asking you about the AI manifesto that Replit’s President Michele Castata published last year. The manifesto makes explicit that you guys are focused on developing what you call ‘ADI’ — Artificial Developer Intelligence.

Castata writes: “We began exploring the idea of developing an ADI because of a simple but powerful empirical observation. Much like Programming Languages (PLs) have been the lingua franca of the computing era, they are also becoming a fundamental language type on which LLMs are trained – as an example, LLMs gain stronger reasoning capabilities when trained on code. Our bet is that the utility of LLMs will grow exponentially as they become capable of creating Agents specialized [in] software development.”

Off the bat, what are the biggest challenges you encounter right now in pushing agents from competent code generators to orchestrators of complex software projects?

Amjad: The main bottleneck is reasoning. Think about how a programmer approaches creating a program from scratch. There’s some amount of planning. For example, a Twitter clone would require some way to persist the data, some way to move the data from the server and query the data, some way to render the posts and so on. You’re going to need to do that — to write a plan — before you write your first line of code. And so right off the bat, for a long time LLMs were not good at planning, and therefore you could not execute complex projects.

But as LLMs got better at reasoning, they got better at planning. And they’ve only recently started creating more plausible plans. In my Ted Talk last year on agents, I talked a lot about agents making plans, because I felt like that was the first step in the journey. We spent a lot of time just trying to get the planning step correct when we were working on Replit Agent.

And so if you’re a programmer, after you plan something, you start writing the code. Typically, you’re just writing prototype. You try to get the system to work, in some capacity, before you iterate on it. And the problem with LLMs for a long time is that they were lazy. You could get them to output one file or function, but it was actually hard for a long time to output an entire project. But now at least some LLMs are more capable of doing that.

Anyway, you write a prototype and more often than not, there’s some kind of error. And so when there’s an error, you need to come up with a hypothesis about why it’s there, you need to validate that hypothesis, and then you need to generate a fix. That’s also reasoning. And then you repeat — ad nauseum. You want to come up with a new feature, so you plan it out, prototype it, fix the errors, polish it and so on.

So the core things are reasoning and feedback. This is what Replit excels at. The interfaces we create for the AI are actually the same interfaces we create for humans; the AI can reach into those interfaces — an editor, a shell, a database, a server – and orchestrate them to build the software.

Sanjana: Does the future software engineer look more like a product manager? Someone who does the ideation and then tasks various agents to execute their plans?

Amjad: It will depend. I think there’s going to be a bifurcation between a software engineer — a person who studies computer science for four years and specializes in some aspect of software engineering — and a software creator. Which, by the way, is why we don’t say we’re trying to create a billion software engineers. We’re trying to create a billion software creators.

In other words: Anyone can take a photo on Instagram, but not everyone’s a photographer. Anyone can use Excel, but not everyone’s an accountant. I think anyone, or most people, will be able to create software, but not everyone is going to specialize and become a software engineer.

Software creators will be more like product managers. I think for a while software engineering will increase in efficiency, but will ultimately not look radically different. I think the thing that will look radically different is the new kind of software creators — the ones we want to create and empower.

After the release of Replit Agent, there is a fundamentally new category of developers. We are creating a new role. And these people need new tools and new ways of thinking about things. We [the Replit team] just spent an hour arguing about what might feel like a trivial decision, but we’re just agonizing over every pixel because we feel like we’re responsible for building a new creative tool, as opposed to just another IDE.

Sanjana: What do these new developers look like? What are they building?

Amjad: It’s very fresh, but I’ll give you some examples. Starting from some of the simplest ones: There are people building software for their families and personal lives. Someone built an app called Chore Hero, which had a leaderboard and scores for his kids about doing chores, and his family uses it every day. Someone created a personal health app where they can track their sleep and exercise and all of that. Someone created an app to teach their kids about colors — how do you blend different colors and what comes out of that. So, there’s a lot of educational and personal software that’s being created. Someone just created a mapping software where they can drop memories, attach multimedia, and visualize their memories over all the different places they’ve visited.

It’s quite profound because, previously, they would’ve had to go to the App Store and look for the thing that matched what they want to do. And typically it’s full of ads and crap like that.

Sanjana: And might be hoovering up your data.

Amjad: Right, exactly. But now you can create software for n=1. I think that’s a really profound new thing. Then, on the business side, I’ve been trying to articulate what those apps are and the best thing I can come up with is that they’re last mile apps or line of business apps. The idea is, you already have the infrastructure in your company. You have the databases, you have the CRMs, you have SaaS tools, and sometimes you just want to move one thing to another place and do a little bit of computation in the middle. Sometimes you want to create a dashboard and mix different data to show something.

Other times, you want to create an application with logic to manage things. We have real estate agents in Ohio building back office apps to track some of their deals and stuff like that. We have doctors creating health dashboards for their clients. We have artists creating showcases for their work. We also have people working at bigger companies building small utility applications. Maybe they’ll upload a CSV for every week of feedback they’re getting on their product, use GPT to summarize that feedback, and so on.

And finally, there’s the startup founder that couldn’t start a company before these tools emerged because they didn’t have time to learn how to code, or didn’t have the patience for it, which is totally valid. Suddenly, they’re enabled and they want to start a startup. We recently talked to someone that’s been a CEO in the Valley for a while and had this standing offer from a private equity firm. After Replit Agent came out, he used it a bit and decided to turn down that PE firm and start a startup. Before, he felt like he was always dependent on a technical cofounder. Now, for the first time, he can just build things himself.

Sanjana: This software creator revolution feels quite powerful in light of what you’ve called the “Steve Jobs blackpill” — this idea that post-iPhone, there’s a sharp divide between active developers and passive consumers of information technology. Most of us are the latter.

What you’re describing feels like it could be a paradigm shift. It could be quite subversive if it gets people off highly centralized tech platforms. If you empower people to create software for their friends and family, then you’re undermining the huge data extraction economy that lots of people feel hopelessly caught up in.

On the other hand, if you tell most people now that maybe they’ll be creating software in ten years, it’s a bit like telling people in the eighties that they’d have a personal computer in their homes. They’d be pretty confused. They probably wouldn’t understand why. Have you found ways to make this idea make a bit more sense to people?

Amjad: The early adopters are probably a bit weird. There’s a bell curve of adoption discussed a bit in a book called Crossing the Chasm, and the idea is you have early adopters, late early adopters, and then the general population around the middle of the normal distribution, and then late adopters.

So basically, when you release a new technology or product, at first you’ll mainly get users that have been searching for something like it in some capacity. I think it will take a while for us to reach the everyday person. And what you said is absolutely true — we need to find a way to change our messaging in order to relate to them more, which I don’t think we’re doing today at all. We haven’t really found a way to talk about what this [Replit Agent] is to someone who isn’t searching for it.

I guess I’d describe a user journey that they might’ve had. They need to get something done, say edit a video. They go to Google, they search for that thing, they click on the first website, and it turns out it’s not exactly what they want. The second website is full of ads, you can’t use it. The third website doesn’t work. They spend an hour searching for the thing that they want and then maybe settle for something, pay for it, and then find out it doesn’t do exactly what they want. So they end up compromising.

But what if when you typed that thing you need into Google, it started building it and then asks you for feedback? You can talk to it like you’re talking to a person. “Oh, actually can you move this here or fix that?” “Can you add this feature, remove that one?” Basically, any time you have a problem that an app can fix, you can just create a bespoke one.

Sanjana: It does feel like as AI agents become more embedded in all aspects of our lives, there will probably just be emergent use cases here that we can’t even fathom right now.

Going back to Artificial Developer Intelligence for a second — it seems to me like that’s a really powerful narrative frame for talking about how AI can positively impact society, as contrasted with the AGI frame. We have lots of people who talk about how we’re going to have this AGI that’s going to make almost all human work superfluous, and maybe we’ll need some version of UBI or some form of Nozickian “experience machine” to occupy ourselves in the future.

Amjad: That’s even more of a blackpill than Steve Jobs.

Sanjana: Definitely. But what you’re describing with ADI is that, no, this thing is going to help us bring our good ideas into reality, but you’re still going to need to be smart — you’re still going to need to think and bring your creativity to bear.

Amjad: Yeah, I think it’s a philosophical difference. I believe humans are special, and my conception of what a computer is and what a neural network does is probably very different than those of a lot of people who believe AGI will usher in an era of fully automated communism, where you’re getting your UBI check in the morning and that’s it.

I do think it would be great if we could work less. I’m not saying AI will not make us work less. I think the best thing about AI is that it takes away the repetitive routine work. I think that’s the core feature of AI, because the repetitive routine work is what’s most represented in the training data. Like, Michael Schumacher is not represented in the Tesla driving data. The creative aspect of F1 racing is not in the middle of the normal distribution, which is what Tesla sees. In some ways, AI is the ultimate midwit [laughs]. It automates commodities and leaves us the artistic and creative things. I don’t think it will take away the human touch. I don’t know of any technology that’s capable of doing that right now, though maybe we’ll get there.

Sanjana: Yeah, AGI language is interesting because the people most obsessed with it seem to think it’s a liberating frame — here’s this tech that will unlock physics, create abundance, and so on — but to the layperson it just sounds quite scary. And so, paradoxically, it invites heavy-handed regulation, because the rhetoric coming out of the industry is so extravagant.

Amjad: Well, they might want to invite regulation. Regulatory capture is a very profitable strategy. Long term markets almost always create nearly perfect competition. Margins compress and industries become more competitive, which is a good thing for humans generally because things get cheaper. But obviously not ideal for businesses.

Now, there are little moats for businesses that are fairly innocent. You can create switching costs. Amazon makes it so that the egress costs of S3 are so astronomically high that no one is incentivized to move from AWS to Google Cloud. Otherwise, the cloud would be a perfectly competitive market. But the other moat you can create is through regulatory capture. If no one else can enter the market because the regulatory burden is so high, then that’s actually a good thing. And so as rational actors, a lot of the big AI corporations might actually invite regulation.

Sanjana: I want to talk a bit about your blog post on “hyperreality,” which you define as experiences that are distilled to their most intense elements. Social media likes are hyperreal, you say, because they excite the mind in a way removed from all of the usual physical and emotional context of embodied life. They are to embodied positive feedback what junk food is to a home-cooked meal.

It’s a pessimistic post. You write: “Religions have dealt with the destructive nature of hyperreality. Why do you think you can't draw pictures of people or animals in Islam? A restriction that generated an art culture rooted in abstract (unreal) shapes. The secular West is especially vulnerable to hyperrealism because societal norms that could protect us are considered oppressive. I love the West's renegade aspect. It resulted in innovative art, science, and technology. But it left us unprotected against hyperreality.” And you conclude with: “Whatever comes next — may be a techno-futurist religion — needs to address this issue.”

First, why should we think we’re not just going to amuse ourselves to death with AI-assisted hyperreality?

Amjad: Yeah, it’s possible. The default path is hyperrealism and hedonism and amusing ourselves to death. I think that’s plausible. On the other hand, I think there are lots of people that are fundamentally unsatisfied with that. And I think in the long term, most people would just be miserable living like that. There will be societal backlash — we’re already seeing that with iPad kids, and with new norms emerging around giving kids access to addictive technology.

Smoking used to be ubiquitous, but now the West has basically completely oppressed smokers, which I think is good. Junk food is going through the same thing. So, I start from a pessimistic view, but I think the optimistic view is you see lots of examples throughout history of society pushing back on destructive technologies.

And I guess where I differ from a lot of techno-optimists is that I actually think markets can be quite destructive. The other day, I saw on Twitter how RFK Jr. was talking about how tallow and animal fats used to be the main cooking oils, but then we switched to seed oils thinking they were healthier, and now we’re finding out that they’re bad for us. And I responded saying that it actually wasn’t like that. Proctor and Gamble actually explicitly marketed toxic material — cottonseed oil, a waste product of cotton farming — to people, and that toxic material turned out to be quite addictive.

So when you fry potatoes in that oil, it can give you diabetes, make you addicted to it, and so on. You need do need to regulate things like that — and that’s a market creation! Basically, I think markets can totally get into a funky place where they’re harming humans. I’m not a leftist in the sense that I think markets are inherently evil, of course not. Also, I’m not entirely sure that government is the best way to push back on markets. It’s a tool, for sure. Religion and culture are other tools. But I think that government is a very blunt tool, one that can create a lot of negative externalities.

As a civilization, I think we need lots of different tools to be able to rein in the destructive aspects of markets.

Sanjana: I’m curious if you can say more about the religion component. It seems to me like there’s this funny thing happening in Silicon Valley where you get these shadows of organized religion, you know, ayahuasca trips and talk of spirituality, and maybe even some vague gesturing towards a form of Christian universalism. Still, it’s quite unstructured, and definitely not prescriptive (or proscriptive) in any meaningful way.

But it sounds like what you’re saying in that piece is we need a kind of genuine religious revival if people are going to make it through a post-Turing Test world where we’ve got agents that can do lots of things we used to, the economy is radically changed, and so on.

Amjad: It’s hard for me to speak to that because I am actually not someone who grew up in a strict religious household. I grew up in Jordan, a somewhat religious country, but both of my parents came from more secular backgrounds. And I also saw a lot of the negative aspects of religion, so I want to bring nuance to the conversation. But at the same time, I think the main thing religion brings us is this realization that, no matter how strong-willed you think you are, you’re probably weak-willed in a very fundamental way. It’s very easy to do things that destroy your life. Addiction is an easy thing to point to. I think it’s probably empirically true that more religious places have less addiction. The fentanyl crisis in the US is probably negatively correlated with religiosity, right? As religion went out the door, drugs came in — probably partly because it left this void of meaning and connection with other people.

Partly, religion can give you principles that feel like they’re outside of you or non-negotiable. There are things that are sins, and therefore you can’t do them or there’s a cultural cost associated. But when you remove that, it’s very easy to follow the immediate pleasures that will negatively impact your life and perhaps kill you in the future.

One way to conceptualize religion is that it’s actually just an adaptive trait. It helps with survival, and it helps with the birthrate. Islam, for instance, explicitly promotes having more children, and if you want civilization to continue, you can’t have birth rates below replacement, right? And what we see is that whenever a place becomes more secular, the birth rate just plummets. That’s not even controversial at this point, it’s just demonstrably true.

But anytime someone starts a new religion, there’s a lot that can go really wrong. Maybe Mormonism is the most successful one in the US, but you’ve also got Scientology, you’ve got Jim Jones. And you probably don’t want a bunch of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs starting your new religion.

Sanjana: Yeah, that would end badly. It’s an interesting thread though, thinking about whether you could tease out those salutary aspects of religion as an institution, those pro-human qualities, and isolate them a bit from the dogmatism. My sense is they’re quite intertwined.

Anyway, moving back to AI. I know Replit has lots of users who are under 18 and live outside of the US, as does Product Hunt. I’m curious if you think the AI revolution will finally shift the locus of tech industry power from Silicon Valley. To me, that feels somewhat thematically connected with the idea of network states and maybe the eventual twilight of the nation state.

Amjad: Yeah, I think the nation state is one of the more brutal institutions that humans have created.

Sanjana: It does feel quite sclerotic and dysfunctional, especially in a place like California. But can you speak to how AI might decentralize access in some ways? And what implications that might have geopolitically?

Amjad: Well, Silicon Valley is actually quite resilient and I think it will always have a special place. But I think it’ll be able to capture less of the value created by software in the future. As more people become software creators and the personal software revolution happens, you’ll have a lot more entrepreneurs creating things solely for their communities and for the geographies that they know more about. I think that’s certainly a possibility, and I think wealth might be more widely distributed and there will be more wealth creation because more people are coming online every day.

In that sense, AI does feel quite subversive. In terms of how it will change geopolitics, though, I think that’s a harder question. In a recent blog post, Dario Amodei [the CEO of Anthropic] talked about how AI would lead to a more democratic world, because you’ll have this globally free information environment that’s hard to censor. I didn’t find that argument very compelling. It felt a bit like an end of history argument.

But it does feel like AI will change a lot. I mean, you can go into Llama now and get uncensored weights and ask questions that are quite subversive. And it’s interesting because the story we tell ourselves about information is that, after the printing press and the Protestant Revolution, we decentralized information. It’s partially true, but at the same time there are still a lot of questions and taboos that we can’t explore. There are a lot of powerful forces that are forcing untruths, a lot of hidden secrets that people don’t have access to. Perhaps I can’t give examples because those are a taboo, right? But the truth is very important, and it shouldn’t be feared, because it’s the truth.

Why fear what’s true? You’re already living it. But there are lots of sort of politically correct ways of lying about those things. I think if a truly uncensored AI becomes the norm, then you can’t really hide the truth anymore. If AI can find untruths and cross reference the news and reason about events in the world, then we might enter a pretty radical world. Because the media is mind control — it’s controlled by a very small number of corporations and people. And AI can be quite destructive to that.

Sanjana: It’s interesting, one of my big realizations back when I was covering local politics was how much government weaponizes obfuscation to prevent people from understanding what’s happening in political processes. You’ll have these hours-long city hall meetings that very few people go to, these 1000-page bills that no one reads, these politicians that talk in a very arcane language of civic codes — and maybe the TL;DR is that they’re just implementing this regressive zoning rule that’s going to kill a lot of new housing or something, but it’s almost impossible for an outsider to discern that.

Amjad: They’re encrypting the process.

Sanjana: Yes. And if AI can decrypt it, and provide people with an unvarnished view of what’s happening politically, then I think that will get quite destabilizing, quite fast.

Amjad: The hope would be that there’s more decentralization of power with AI. I’m sure you’re familiar with The Sovereign Individual. It’s quite a compelling book, though it’s a bit hard to figure out why exactly they think sovereignty will decentralize. It’s something along the lines of the fact that information technology changes the equation of violence, as they call it. When wealth becomes more portable, it’s harder for the state to seize it, and therefore the individual will have a market of different states to choose from.

We’re already starting to see something like that. Estonia had a digital ID or passport that allowed you to apply to become Estonian online. And when nation states start to compete over people, they lose power and the individuals become more powerful.

Sanjana: Quite a prescient book, given that it was written in the late nineties. They predict the rise of cryptocurrency, widespread remote work, online shopping and so forth.

Amjad: Yes, and about how the distance between ideas and wealth will collapse. The idea is that if you're able to think clearly and express what you want to build, you’ll be able to build the thing very easily.

Sanjana: In other words, they predicted Replit. [Laughs]

Amjad: To tell you the truth I’m a bit pessimistic about the idea that nation states will lose power in any meaningful capacity any time soon. They’ll fight to the death, and the intelligence apparatus is quite strong. I’m not sure the authors of The Sovereign Individual fully anticipated how powerful those agencies would become. The nation state is really just an animal, and when an animal is threatened it will defend itself.

Sanjana: You do get the sense that our executive branch of government is just an agglomeration of three-letter agencies at the moment…

Amjad: Yes, it’s a Kakfaesque nightmare in a way. And yet, for many of us America is still the best place to create wealth. The government is just this big machine, slurping up the wealth, transforming it into debt, and now we’ve got to pay interest on the debt.

Eventually, something needs to happen. But right now, a lot of our lives are still fine, which is good. I hope they continue to be fine.

Sanjana: Indeed.

Bringing this back to Product Hunt — if you’re thinking about a young person today who’s trying to anticipate the economic changes that AI will bring, what do you think they should do to equip themselves for success?

Amjad: If I were 16 or 17, I’d probably want to get really good at AI. I’d want to really understand it, to be able to fine-tune it and have an intimate feel for how it works. In the same way that in 1993 I saw a computer and learned to understand it, I think kids nowadays should work hard to conceptualize how an LLM thinks. Because if you know how it thinks you’ll be able to prompt it well and you’ll know what kind of things you can build with it. You’ll know what’s on the other side of the product — or of the propaganda.

Right now, for instance, I can really detect LLM writing. On X, I can instantly tell when something was LLM-generated. I spent so many hours playing with them that I’ve got a pretty good intuition about what they are.

I really think that everyone growing up today needs to understand the mechanisms underlying LLMs. On top of that, I think being creative — being generative — is very important. Being able to generate a lot of ideas is more crucial than ever. Jobs are going to be less routine and more creative, and the value of creativity will be a lot higher. Also, you’ll be a much more interesting person if you’re creative. A lot of repetitive work will be done by machines, so the only way to be interesting is to have novel thoughts, interesting things to say, creative or artistic projects to pursue. I’d spend a lot of time on that.

And I’d try to be global in my perspective. Maybe the future is network states, maybe not. But locality will probably be a lot less interesting in many ways. You’ll probably find people that are a lot like you on the other side of the planet. So traveling, speaking multiple languages, familiarizing yourself with geopolitics and what’s going on in the world — those are all important.

Sanjana: Though in a post-Covid world, it does feel like we place this renewed premium on in-person interactions. Ten years ago, it felt like we were all very insouciant about the possibility of complete remote work, and I think we’ve moderated a bit on that…

Amjad: Although, we now all use Zoom for meetings. Most of my meetings outside of my company are Zoom meetings. I think a lot of people are more comfortable doing business without ever meeting people. VCs used to never close deals without meeting in person. Now they do.

Sanjana: Shifting gears back to Replit — why does it seem so difficult to shift code from local environments to the cloud? We’re quite comfortable with using Figma for design, Google Docs for writing, online spreadsheets, and so on. Why is code different?

Amjad: I think programmers tend to be quite rigid. I’m not sure why. Software requires a lot of flexibility, but engineers tend to be quite rigid in their tools. You can see it in the kind of software they choose. There are a lot of people that still use Emacs and Vim. If I were to psychoanalyze them, I might say that maybe there are just so many aspects of coding that are multivariable, that psychologically they’re attracted to having predictable, familiar tools.

I mean, we can see this with languages. Take C. We’ve been plagued by memory safety issues and overflow bugs in C for a long time. The most frequent security bug is buffer overflow. A language like Rust almost completely removes that, but it’s taking a lot to get people to adopt it.

Despite the fact that programming is a young industry, it’s quite a rigid industry. It’s not inherent to programming, it’s inherent to programmers. And that’s why we’re focused on a new generation of programmers.

Sanjana: Ok, one final question: What are you most excited about in the near future for Replit?

Amjad: I am really excited about this idea of empowering small business people — small-time entrepreneurs and self-employed people — to build things for themselves. I want to make this mainstream. And I think over the next two or three years we might see this becoming, if not a mainstream thing, then at least something a category of knowledge worker is using.

Scale is going to be important, and our team is buzzing with ideas about how we can use the data and feedback we’re getting from users to improve the product. I think the more people use the product, the better it will get — and then hopefully it will just improve at an exponential rate.