I started Aalo back in 2017, after realizing that furniture shopping tends to be full of compromises. Affordable "fast furniture" employs low-quality materials, and high-quality brands usually require a big budget. On top of that, I couldn’t find a furniture option at any price point that was flexible enough to adapt to my frequently changing space needs. Given my background as a manufacturing engineer—I was working for Lexus, a division of Toyota, at the time—I set out to tackle this problem.

While thinking about how to build a more attainable, adaptable, and sustainable furniture option, I took inspiration from some of the key aspects of the Toyota Production System, particularly the concepts of "elimination of muda (waste)," “genchi genbutsu (go and see the problem),” and "kaizen (continuous improvement)." By maximizing the use of common parts throughout the product line, I realized that we could eliminate a lot of inefficiencies in manufacturing and logistics, while continuously expanding the applications of the modular system.

I iterated on these concepts as I learned how to build my first product, and again as I prepared to debut my 2.0 line, which includes a modular side table, garment rack, coffee table, desk, and bookshelf.

In this photo essay, I’ll show you how I adapted my designs and landed on the project I’m launching on Kickstarter now.

The sky’s the limit for first prototypes

My initial idea for Aalo was to build an all-in-one DIY system capable of building furniture or any other kind of structure—almost like Lego for practical uses. I started with an open-ended approach, designing as if there were no constraints in cost, manufacturability, or functionality.

These early concepts had multiple custom parts and complex geometry, making them almost impossible to be mass produced at a reasonable cost. They also needed a good deal of improvements in fit and tolerancing, but it was a great exercise in thinking about what kinds of designs could be possible. During the ideation stage, the bulk of my time was spent surveying people both online and in person to figure out if others also saw a need for such products. After doing over 200 surveys, I noticed that most people’s interest in customized structures revolved around furniture, and many people did indeed share my frustration with the dichotomy of “fast” versus luxury options.

Fast iteration through 3D printing

Thanks to the increased accessibility of 3D printing, going through the first handful of prototype concepts was a breeze. At this stage I explored a variety of ideas, from self-clipping connectors that required more than 200 pounds of push force to engage (impossible!) to more refined connectors that utilized a plastic locking insert or spring lock. Through this process, my knowledge in 3D printing and rapid prototyping grew exponentially, and I began thinking about ways to cut prototyping costs and increase efficiency even further.

Finding the limits of 3D tests

After more than 20 different concepts, the first item tested on a fully assembled design was the connector with locking spring clips. One challenge I encountered at this point was that I needed more than 10 sets of connectors to do any meaningful assembly tests. High quality (SLS) 3D printing had long lead times and was quite expensive, so I got creative with DIY molding and hand forming methods to cut time and cost. Plastic concepts worked well for visualizing the idea, and I was getting more confident that the interchangeable connector system could actually work, but I still wondered how I would ever be able to accurately test the manufacturability and strength of the furniture with just 3D-printed plastic parts.

Turning to suppliers reveals new setbacks

I started a month-long search for die casting, continuous forming, and extrusion suppliers (for the connectors, spring clips, and beams, respectively). Die casting and extrusion methods are some of the most economically viable aluminum manufacturing processes, so my design for manufacturing (DFM) focused on these methods. I sought out suppliers who would agree to make small sample runs, and after hours of meetings and design reviews, I finally had my first production samples in hand.

These samples helped shine a light on many problems that I hadn’t encountered before. First of all, the connectors were way too heavy, due to their unnecessarily thick cross section, and the spring clips were almost impossible to remove once attached to the beams. The difference in flexibility between plastic and aluminum parts made the spring clip design difficult to assemble—and not reusable. I felt defeated, but I learned exactly what to expect from manufacturing. To keep the principles of “eliminating muda” and “kaizen” in check, it was time to go back to the drawing board.

Back to the drawing board for a more lightweight concept

After many more iterations, I finally settled on a concept that would become the first version of Aalo’s commercial product. The new connector design had mirrored top and bottom components with thin walls, which weighed 70 percent less than the previous concept and eliminated the need for spring clips. Finally, a functional minimum viable product (MVP) was born. I had been developing this for eight months, and I couldn’t wait to see what consumers would think of Aalo. Even before figuring out manufacturing, I put together a landing page and started spreading the word through online communities such as Product Hunt and Reddit.

I learned—the hard way—that I really should have checked my factory’s work

The hard work seemed to have paid off, and I felt ecstatic to have my first paying customers. However, what followed is a tale that most hardware founders know all too well.

In order to get a small batch of the parts manufactured as soon as possible, I rushed back to the manufacturers to put in a new order. A local supplier made the extrusions, so I was able to keep a close eye on the process, but the communication with overseas suppliers was difficult to manage. Despite many warnings, I made the mistake of not flying over to physically check the quality of the parts while I had the chance. When the initial batch came in, every single connector had a defect where a critical piece of end bit was missing from the design, even though the quality inspection report had all the right numbers. Panic and anxiety kicked in. I knew this meant significant delays fulfilling orders for the customers who were so excited to support Aalo.

Processing orders with friends and family was fun, but not scalable

The whole ordeal taught me to never cut corners on quality assurance, no matter the cost. Thinking that it’s better late than never, I flew over to China to kick off production with a more qualified vendor we met through a fellow entrepreneur. I spent over a month there to make sure the parts were up to spec. By this time, we had 60 preorders waiting to be sent out. I went back to Canada and began cutting, packaging, and shipping all of the orders day and night with the help of my close friends in a small warehouse I rented.

Another lesson learned? Help from friends and family is definitely not scalable, and your time is valuable. Factor the labor, post-production, and packaging into your cost of goods from the beginning, as it can make or break your business model later on.

Continuous improvement through customer contact

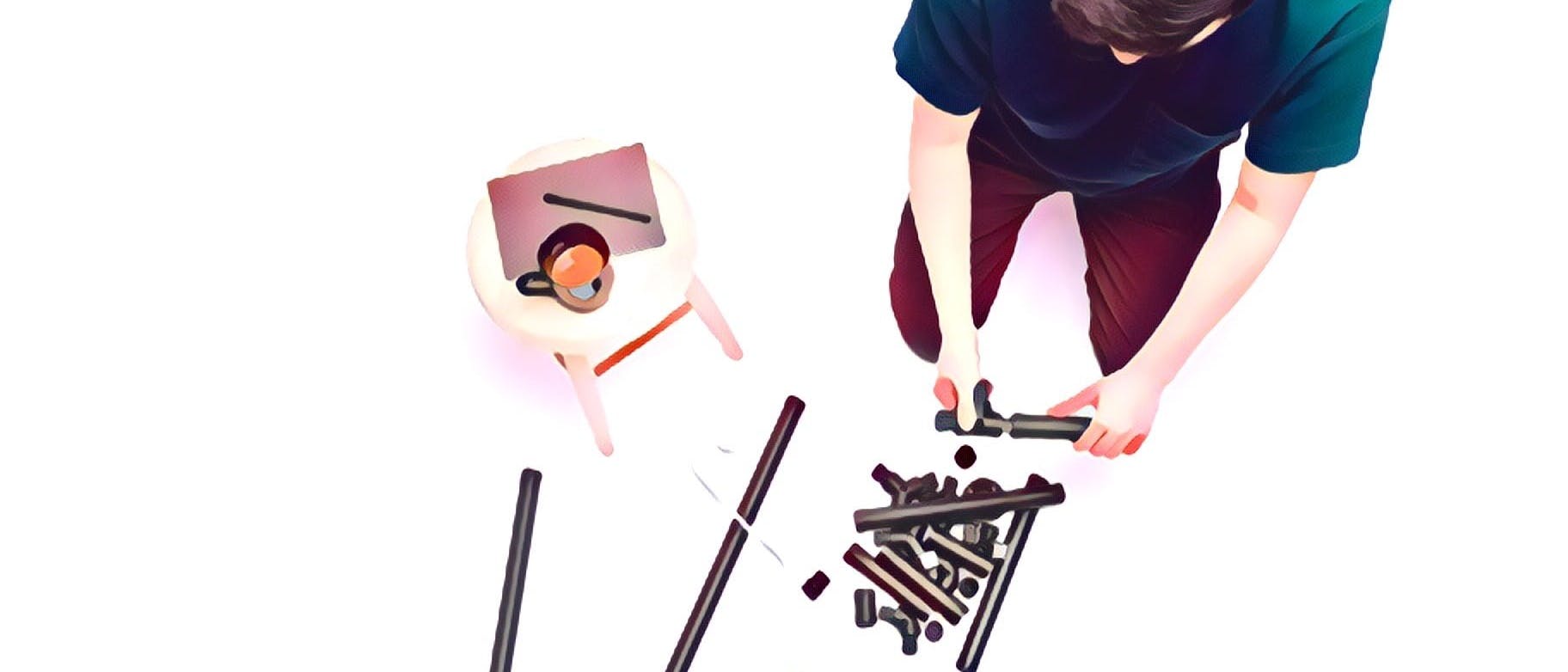

Now that orders were being shipped out, it was time to collect feedback from customers and hear what they had to say. The best way to do that? Watch them assemble your product! I made a total of 12 visits to different customers’ homes in California and Canada to interact with them and get their thoughts. Everything from first impressions to opinions on the assembly process was crucial to the Toyota continuous improvement (kaizen) philosophy I wanted to bring into my work.

Setting up logistics was challenging, but I was able to do it because my gracious customers didn’t hesitate to let a stranger (me) walk into their homes to watch them assemble Aalo. Feedback gathered from this experience became the foundation of Aalo version 2.0.

Introducing Aalo 2.0

Aalo 2.0 is a culmination of a year and a half of development and customer feedback, and it’s an improved model in multiple aspects. The connector material was changed to zinc to give it 40 percent more load-bearing strength and six times better impact strength, and the tips now have a grooved profile to provide better grip during assembly. As for the beams and panels, the slotted portions are designed to be snap-fit, so that assembly is now much easier even for bulky items.

With the launch of Aalo 2.0 on Kickstarter, we want to introduce our new product to this forward-thinking audience and build an even stronger community to fuel our future growth. We’ll continue to stay true to our philosophy of continuously improving our products to be better in every aspect, and to build the world’s most flexible furniture system.

Aalo is live on Kickstarter through June 8, 2019.

Kickstarter just turned 10. This photo essay by Sejun Park is part of a series that celebrates past projects and introduces a few new ones. Read more here.